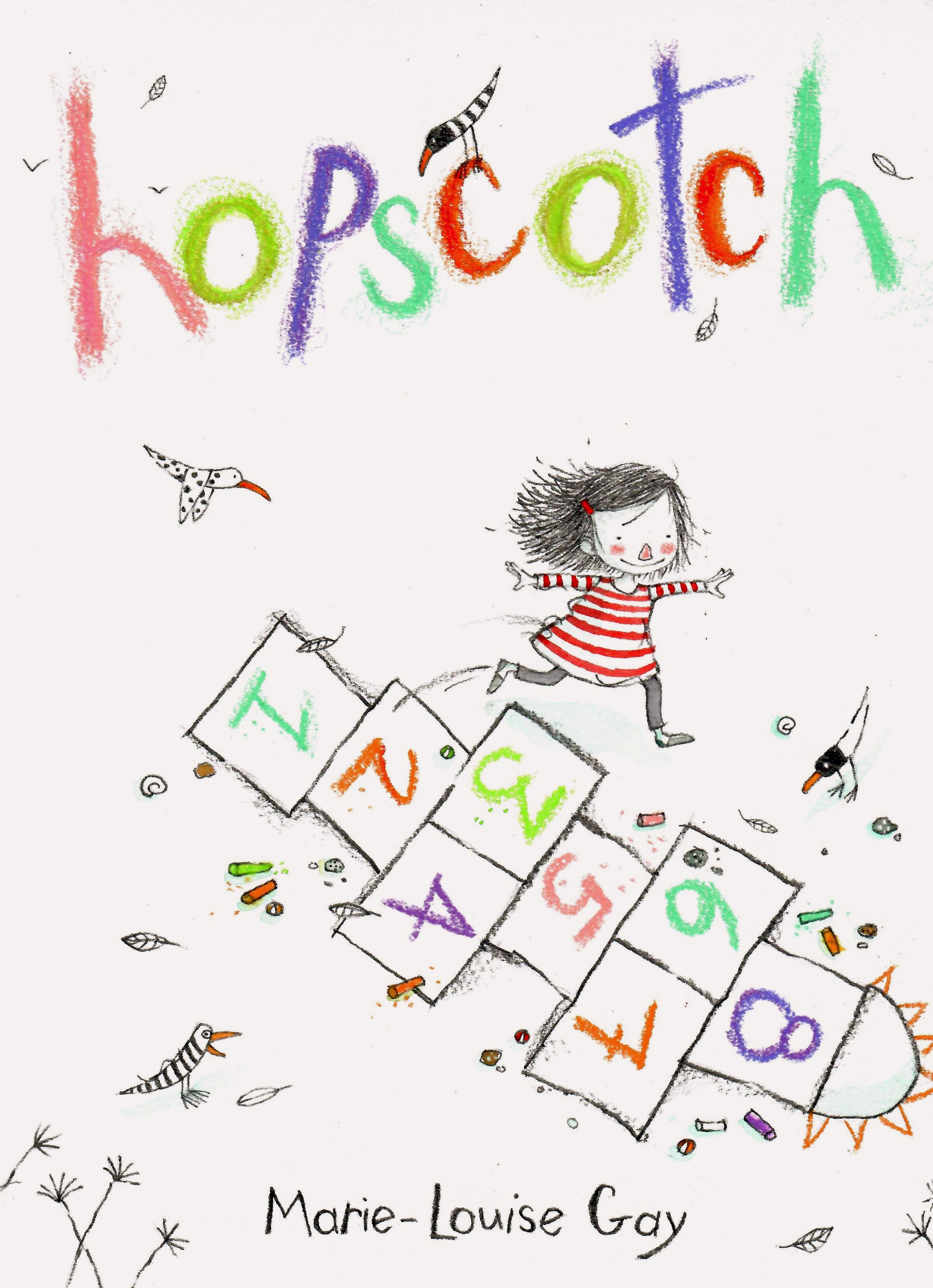

HOPSCOTCH

The following is an interview I did with OPEN BOOK in August 2023, for the full article go to :

For a kid, moving to a new house and finding friends in a new school can be extremely tough. In iconic KidLit creator Marie-Louise Gay's new picture book, Hopscotch (Groundwood Books), Ophelia uses the power of her imagination to make a new, painful situation feel magical instead of intimidating.

At first, Ophelia's hyper-charged imagination is working against her: with Gay's trademark creativity, we see giant rabbits with sharp teeth at her new house, scary ogres on the way to school, and crow-witches in the trees as Ophelia can't help but imagine the scariest version of her new life after yet another move.

But when she arrives in her new school, with everyone staring at the "new kid"—the only one who doesn't speak French—Ophelia puts her whimsical, powerful imagination to good use, creating her own kind of magic and connecting with her new classmates.

A story of the big feelings of childhood, Hopscotch is Gay at her best, acknowledging the rich, vast world of childhood and the depth of kids' emotions and experiences, as well as the power of their creativity. Hopscotch's intimate storytelling and lush, whimsical artwork draws close-to-home inspiration from Gay's own childhood in Quebec.

We're excited to welcome one of Canada's most talented kids' book creators to Open Book today as part of our Kids Club interview series. Gay, who is known for her beloved storytelling including the popular Stella and Sam series, tells us about how she finally came to be ready to let readers get a glimpse of her own childhood experiences, explains why she loves the freedom of not knowing a story's end when she starts writing, and shares her two strategies for getting through a project's toughest points.

Open Book:

Tell us about your new book and how it came to be.

Marie-Louise Gay:

Over the years, since I wrote the Stella and Sam series, I have been struck by the fact that people ask me over and over again if Stella was me as a child. Was Stella's childhood similar to mine? Was Stella one of my children? As it is often said, writers put a little bit of themselves in every one of their characters, so I can truthfully say that Stella resembles me in certain ways, mainly for her optimism, her whimsicality, and imagination. But my childhood was different, not as easy-going or as carefree as in the Stella series. I finally understood that I had written the Stella stories as a way to recreate the childhood I wanted to have. So I decided to revisit an uncertain, precarious time of my childhood and see what kind of story would emerge. After all, writing is a process of discovery.

It became the story of Ophelia, the little girl who is the main character in Hopscotch, who lives in a family that moves around a lot. She often has to leave friends and stability behind. Like Jackson, the tiny dog who lives next door, and who was soon to be her friend, but who disappears just before Ophelia has to move again with her family. Ophelia despairs of ever seeing him again even though, she tells us, "Every day I cross my fingers and wait for Jackson to come back. At night I make a wish on every shooting star. I rub the magic stone I found in my yellow rain boot. I draw a magic hopscotch. I hop forward on one leg, I hop backward with my eyes closed..."

Ophelia believes in spells, charms, magic, and enchantment, and has a vivid imaginary world where giant rabbits roam and crow-witches cackle in the trees that tower over her temporary home in a decrepit motel. She meets a huge ogre on her way to her new school where she finds out what her mother hadn't told her: everybody speaks a language she cannot understand. Even the fairy princess teacher. Ophelia is sad and scared and lonely, but is also resilient and creative and manages to find a way to cope with her dilemma. The story is fictional, though based on some elements and memories that have stayed with me since childhood.

OB:

Did the book look the same in the end as you originally envisioned it when you started working, or did it change through the writing process?

MLG:

I think that every book that I have written and illustrated has taken a different route than the one I envisioned at the very beginning, when ideas float around and are not tied down yet. I think it would be tedious and frankly boring to follow word by word a preconceived scenario to the very end. I actually never know the ending of a story when I start writing and that is important because I feel free to wander off the beaten track, to change my mind, to backtrack, to expand my ideas in other directions.

An outstanding example of this is my book Caramba. For three years I wrote and rewrote a story about a little boy and his cat whom he loved more than anything or anyone in the world. I wrote and illustrated lovely scenes of tenderness and complicity. It was a lovely idea but it wasn't compelling. There was no conflict, no resolution. I dropped the boy character and there was the cat all by himself: "Caramba looked like any other cat. He had soft fur and a long stripy tail. He ate fish. He purred. He went for long walks. But Caramba was different from other cats. He couldn't fly." Just like that, the story went in another direction.

In Hopscotch, I wanted to explore certain events and emotions in my childhood, a story that would be in part autobiographical but very much fictional. I ended up exploring the border between reality and a vivid imaginary world that children cross into so easily when they need to understand and absorb, in their own way, what is happening to them. Their imagination is also a place of refuge and hope. I remembered how I believed in superstition and magic when I was young: crossing my fingers, not stepping on a sidewalk crack or wishing on a shooting star. I expanded and enlarged the presence of magic and imagination in Ophelia's story and everything came together. It made me aware that the story could speak in a subliminal way to children who would identify with the underlying emotions of sadness, fear, uncertainty and loneliness which are part of many children's childhoods. Then they might understand that imagination and creativity can become a form of resilience.

OB:

How do you cope with setbacks or tough points during the writing process? Do you have any strategies that are your go-to responses to difficult points in the process?

MLG:

I have two strategies: I either drop everything, stop writing and engage in a physical or manual activity: gardening, cycling or walking. I try to empty my mind of any thoughts about the story that I have been working on. This creates a space where eventually new, fresh ideas might appear.

Or I switch to my other creative process which is, of course, drawing. I sketch and draw randomly, letting my pencil lead the way, I draw shapes that become people or animals or fantastic objects, I play with colours and forms, I let my mind wander and meander until ideas emerge from this form of visual meditation: a new character who could possibly intervene, a different landscape or setting that would affect the course of the story. I might also start exploring the various emotional states of my hero through facial expressions or body positions. In short, I spend hours drawing and sketching until I find my way back into my story. Then I go back to writing. I write with words as well as with pictures.